Economics by Quint the golden retriever: Sustainable Systems

A 15 min read/22 min listen on how communities develop sustainable solutions for the tragedy of the commons, without government bureaucracy or corporate monopolies.

Authors Note: I’ve got a poll going on the next topic arc you’re most interested in. Let me know here on LinkedIn.

The way I explain it to guests when they visit is that Quint, my golden retriever, chooses people. You’ll know it if you are chosen. Quint will “post up” next to you. If you’re standing, he’ll find a spot and lean in. Sitting? He’ll try to “sneak” onto your lap.

Quint is large and heavy, but he is also a gentleman. He will respect your wishes if you ask him to get down. He’ll attempt to post up later, you can be sure of that.

You have been chosen.

As loving as he is with his humans, Quint has an aversion to male dogs. He gets protective and makes his voice heard. It’s difficult for me to reconcile his affection for humans and suspicion of other dogs. I suppose Quint is a lot like humans in that way.

Quint discovers “the Yard”

I tensed up when Quint let out a guttural growl on our walk. It meant there was a dog around. A dog we didn’t want to cross paths with. It made me nervous when Quint was reacting to something I didn’t see.

It was the spring of 2020. We moved to Lincoln Park in Chicago that winter. We were just getting to know the neighborhood. This was a slow process as walking Quint involved a lot of zigs, zags, and u-turns to avoid conflict with other dogs.

What’s he growling at? I wondered. The street ahead of us was deserted.

I pulled his leash close and walked forward. My golden retriever is hardly a pointer, but it was obvious he was concerned about something on the opposite side of the street. I lifted my hand, squinting against the rising sun.

That’s when I saw it: the Yard. An abandoned parking lot resting peacefully in the middle of our residential neighborhood. I relaxed. It was fenced on all sides, with a concrete wall at the back. I must have walked by that ally several times and never noticed the lot, with tufts of fresh grass poking through its cracked pavement and trees that reached across the fences from neighboring lots, stretching for a bit of extra light

The reason for Quint moving to Defcon 5 was obvious: Two labradoodles, off leash. One gleefully chasing a tennis ball thrown by the owner, not a care in the world. The other standing alert, nose sticking through the chain links, staring Quint down.

“Leave him alone, Jessie.” The owner ordered in a firm tone, “He’s just fine and so are you.” I could see his silhouette giving me a wave.

I waved back. “You think anyone can get in there?” I asked Quint aloud. I looked at the owner, throwing balls to his two energetic laberoddles. The Yard seemed perfect for dogs like Quint and I had wanted to teach Quint to retrieve for a long time, I just couldn’t find the space to do it. What were the rules of this place? I wondered. Who could use it…and when?

A Yard’s Got to Have a Code

I quickly learned “the Yard” (my words, no one formally called it that) was a small institution in the community. If you had a dog like Quint, it was a safe place to let them run around and chase tennis balls off leash. There was also a set of unwritten rules. The first was more of an assumption. The people who knew about the Yard all had two things in common: they were locals, within walking distance and they had a dog (or two or three) they couldn’t take to a dog park. They key assumption was that dogs in the yard didn’t play well with others.

The other “rules” followed that assumption and were fairly simple.

One owner in the yard at a time.

First come first serve.

Don’t hog the yard.

Here’s the amazing part, and the link to our economic theory today: no one governed the Yard. The rules weren’t formally written. Community members just figured it out through everyday interaction.

Let me give you an example.

A tall concrete wall separated the Yard from the alley. The single point of entry was in. So it was hard to see inside the Yard until you were, in fact, inside the Yard.

“Oh I’m sorry, I didn’t see you here.” A dog owner said, quickly escorting her beagle back out of the corner entry. (First come first serve.)

She turned to her dog, who’d begun tugging at his leash to get at Quint. “NO Skip, let’s go.”

Quint, having just retrieved a tennis ball, locked eyes with the beagle invader. I grabbed Quint’s collar. (Assume that dogs in the yard don’t play well with others.)

No worries,” I said, “We’re wrapping up in 5 minutes.” Giving her a polite wave as I kept a firm grip on Quint. (Don’t hog the yard.)

Five minutes of tennis ball throws and retrieves later, Quint and I left. I waved to the other owner, who had waited in the alley for their turn. She and her dog went in. Soon I could hear the beagle happily scampering about. (One owner in the yard at a time.)

I’d had a few interactions just like this. Sometimes the roles reversed and I waited while another dog/owner finished. Other times I emerged from the Yard to find a small line had formed. Crucially to our theory, all interactions with other dog owners reinforced the same set of rules, rules that allowed all of us to coordinate our use of a common space.

It’s hard to understate how against the grain these unwritten “rules” of the Yard are in a place like Chicago. We are a land of bureaucracy. The Windy City, whose nickname was earned not because of the cool breeze off Lake Michigan, but because our politicians will not stop talking. Chicago endlessly writes and rewrites and revises rules.

So who gets credit for the rules of the Yard? Rules I found easy to follow, even though there was no centralized governance to communicate the rules and no market to ensure efficiency?

According to this week’s economist, Elinor Ostrom, the community gets the credit. Her work shows communities do not necessarily need a heavy handed government bureaucracy, strict privatization laws, or an aggressively free market to efficiently allocate resources.

Context: the tragedy of the commons

In our tragedy of the commons arc, we’ve looked at fundamental ideas that shape economic thinking.

Mancur Olson - collective action problems - the tendency for humans to wait for others to act when problems impact a group

Ronald Coase - privatization and low transaction costs as a solution - government’s role in creating the conditions under which conflicts can be resolved quickly and markets can thrive

Garrett Hardin - the tragedy of the commons - humans tend to overconsume common resources (sometimes privatization and low transaction costs don’t work as we’d like)

In my own education, Hardin’s “tragedy of the commons” came early, right after supply and demand graphs in microeconomics class. I liked learning the economics, but it bummed me out a bit. It felt like humanity was doomed to ruin not only Hardin’s cow pasture, but forests, rivers, oceans, the entire planet.

It was similar to studying Hobbes in my first civics class. He described human life in the state of nature as "nasty, brutish, and short" and proposed that, without a king, a Leviathan, human survival would become a "war of all against all." There was a certain ease in the idea of Hobbes’ certainty in his “one right answer,” but that answer made me sad. The only kings I was a fan of were in Narnia, and they shared power.

It turns out, I only had to look around me to see alternatives to Hardin and Hobbes: kind neighbors, libraries, volunteers, and community organizations all around.

Elinor Ostrom, the economist we’re focused on this week studied a range of solutions to the tragedy of the commons. Unlike the “one right answer” approach, the examples vary widely, and range from utopian to gritty in their implementation. There’s complexity in Ostrom’s work but it fostered hope as well.

Economics: Elinor Ostrom and Governing the Commons

Elinor Ostrom won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009, the first woman to receive the honor. Her book, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, argues that the commons don’t have to be as tragic as we’ve made them out to be.

Her work focuses on common-pool resources like the ones we've frequented in this series of posts: fishing in lakes or oceans, logging forests, or grazing on shared lands.

Common pool resources have 3 traits

resources that are accessible to multiple users…

but where one person's use diminishes the availability for others…

and it's difficult or costly to exclude individuals from using the resource

You could even add a box of Lucky Charms on the family dining table to our list of examples

Lucky Charms are available to all siblings…

It’s hard to exclude anyone

Every sibling who digs in leaves a little less for the rest.

But that’s another post. The point Ostrom is trying to make is that, traditionally, common-pool resources are boxed and labeled “tragedy of the commons” and written off as hopeless cases when they can’t be easily privatized or run by big government.

Ostrom disagrees.

She acknowledges Ronald Coase’s solution of clear property rights and low transaction costs, but argues that it’s not the only solution. Ostrom directly challenged Hardin’s assumption that our only tools to prevent overuse of common resources are either privatization or centralized control. To Ostrom, the tragedy of the commons isn’t human destiny. Communities can, and do, develop sustainable ways to share resources like grazing pastures, oceans, and forests. She did a lot of groundwork showing humans were capable of an entire spectrum of solutions and tools that help us live together and live sustainably. Let’s look at a couple examples.

Cattle Grazing in the Alps

If you’re going to provide alternatives to Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons”, it makes sense to start with his example: cattle grazing on common fields. Hardin points out every farmer’s individual incentive is to add more to their herd. In his example, each farmer does this until the common pool resource, the field, is exhausted and the cattle starve.

In the high Alps, particularly villages like Torbel in southern Switzerland we find a counterexample: farmers have managed summer grazing pastures as a common pool resource for centuries. (I had to read that twice: centuries.)

They operate under clearly defined rules: livestock quotas, seasonal schedules, and collective maintenance routines. These communities decided who could graze, how much, and enforced their rules all by themselves, preserving a sustainable solution that allowed the fields to re-grow.

Lobsters and Harbor Gangs in Maine

The Maine lobster industry is a standout example of how local lobster trappers self-organize to sustainably manage a common-pool resource. Lobstermen form "harbor gangs", small territorial groups that define exclusive fishing zones, monitor each other, and enforce unwritten rules on trap limits. Those who don’t follow the rules or outsiders attempting to intrude face swift sanctions, like gear sabotage, which deters overfishing.

Even more fascinating is the role of government: The state does not attempt to dismantle or replace the harbor gangs’ territorial norms or unwritten rules. It largely defers to these local systems of enforcement. The state supports conservation via size limits, bans on egg-bearing lobsters. It does still enforce laws, but it acts in partnership with local communities.

The idea of state government ceding local enforcement to a harbor gang may seem like a rough solution (see link to James M Anderson’s book ) this blend of local self-policing and supportive government actually reflects Ostrom’s “polycentric” ideal because decision-making is collective and local.

Quick explainer: in a polycentric system, multiple overlapping decision-making centers like local groups and state agencies work independently and coordinate to manage resources. According to Ostrom this can get complex, but polycentric systems outperform both top-down regulation (big government) and privatization (a monopoly power). It has helped Maine maintain stable and even increasing lobster stocks over decades, defying the "tragedy of the commons" scenario.

Patterns of Sustainable Harvesting:

Cattle grazing in the Alps and lobster trapping in Maine are two of her most cited examples, Ostrom found many many more.

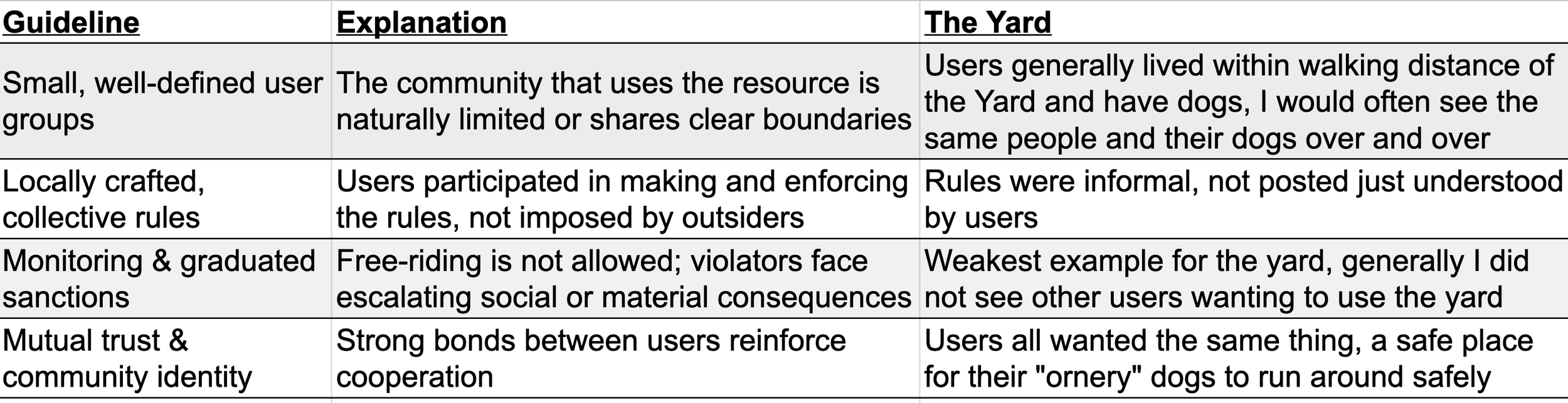

Let’s turn our focus to simplifying some of the complexity. What pattern does Ostrom consistently see for successful methods of governing the commons? (*Note: For simplicity I distilled Ostrom’s patterns and guidelines down to 4. If you’re interested in reading more, here’s a good article.)

4 of Ostrom’s Patterns and Guidelines

I like to think of these less as rigid laws and more like a Pirates’ Code: flexible guidelines. Not every case needs all of them. Take the third item, monitoring and graduated sanctions, and its application to the Yard. There weren’t many competing users, so monitoring wasn’t necessary and sanctions would’ve been overkill. We didn’t need monitoring to share the common resource effectively. So there was none. That’s part of the beauty of what Ostrom found: self-organizing groups often find a cheap and efficient equilibrium. They follow the principle of doing only what is needed.

In contrast, monitoring and enforcement play a critical role in places like the Swiss grazing commons or Maine’s lobster fisheries, where overuse is a real risk. The principle stays the same—but the local application varies.

Budgeting

Compare this principle of only using what’s needed to a familiar phrase from business and government budgeting:

“If we don’t use the full budget this year, we’ll lose it next year.”

The logic that goes unsaid? “So let’s spend it all, whether or not we need to.”

It’s a small example of how organizations, especially large ones in both government and business can drift toward inefficiency. They lose sight of what’s actually needed. Ostrom’s work reminds us that, when local actors are trusted to govern shared resources, even complex, overlapping (polycentric) systems can outperform top-down regulation by and privatization in business.

Conclusion:

Quint is a good boy, mostly. It wasn’t until he and I discovered the Yard that I realized we were part of a group that self-organized: dogs that didn’t get along with other dogs, and their owners.

The Yard and its unwritten rules were great for me, Quint, and Remi (who showed up soon after the Yard was discovered). Elinor Ostrom’s work showed me that this kind of setup isn’t unusual. All over the world, people create sustainable, working systems to govern common resources, and they don’t need to wait for Hobbes's Leviathan to do it. That gives me hope.

When I look back at that spring morning walk with Quint, I see more than a kind dog owner throwing tennis balls. I see the kind of quiet, shared logic that economists like Ostrom spent a lifetime defining. Maybe we humans don't always need the perfect “one size fits all” rule, corporate hierarchies, monopolies or kings to share resources sustainably. Maybe we just need the right people, a little space, and maybe a growling golden retriever, and a few other dogs, to bring us together.

Quint and Remi in the Yard. Thanks to Israel Malovani for taking these photos.