Economics by the Lorax: Local Control

Authors Note: This is our last entry in the tragedy of the commons arc.

I’ve got a poll going on the next topic you’re most interested in and as I write two candidates are in a dead head. Vote for your topic here on LinkedIn.

Also: the audio will be posted this afternoon (when my girls are napping). Sorry for the delay.

The Lorax is one of my favorite childhood books. Like many works by Dr. Seuss, its sing-songy rhythm and read-along rhyme hide deep seeds of wisdom as timeless as time.

Our narrator, the Onceler, who we know nothing of finds themself in a forest, and falls into love.

“And I first saw the trees! The Truffula Trees! The bright-colored tufts of the Truffula Trees! Mile after mile in the fresh morning breeze.”

We see the Onceler’s actions, just his arms and his deeds. We witness them chop one, just one, of the beautiful trees.

Out pops the Lorax, a prophet of sorts, who answers the chop with demands and retorts.

“Mister!” He said with a sawdusty sneeze, “I am the Lorax. I speak for the trees. I speak for the trees, for the trees have no tongues. And I'm asking you, sir, at the top of my lungs-- he was very upset as he shouted and puffed-- What's that THING you've made out of my Truffula tuft?”

What follows is a crash course in the battle between extraction and preservation. The Onceler’s insatiable business demands the chopping of more truffela trees. As the business grows, and more trees are chopped the Lorax continues to rage against the growing machine. But the Lorax’s words are like the sirens caught in a traffic jam: ignored, powerless, noise. The Onceler’s actions do not change. As Garrett Hardin’s predicts in “The Tragedy of the Commons”, the trees are over harvested. The forest slips away before our eyes. The Lorax decries each step towards ecological collapse yet the Onceler continues to expand, overwhelming the ecosystem, until what was once a paradise is now a desolate wasteland.

The Lorax, with no trees left to speak for, leaves.

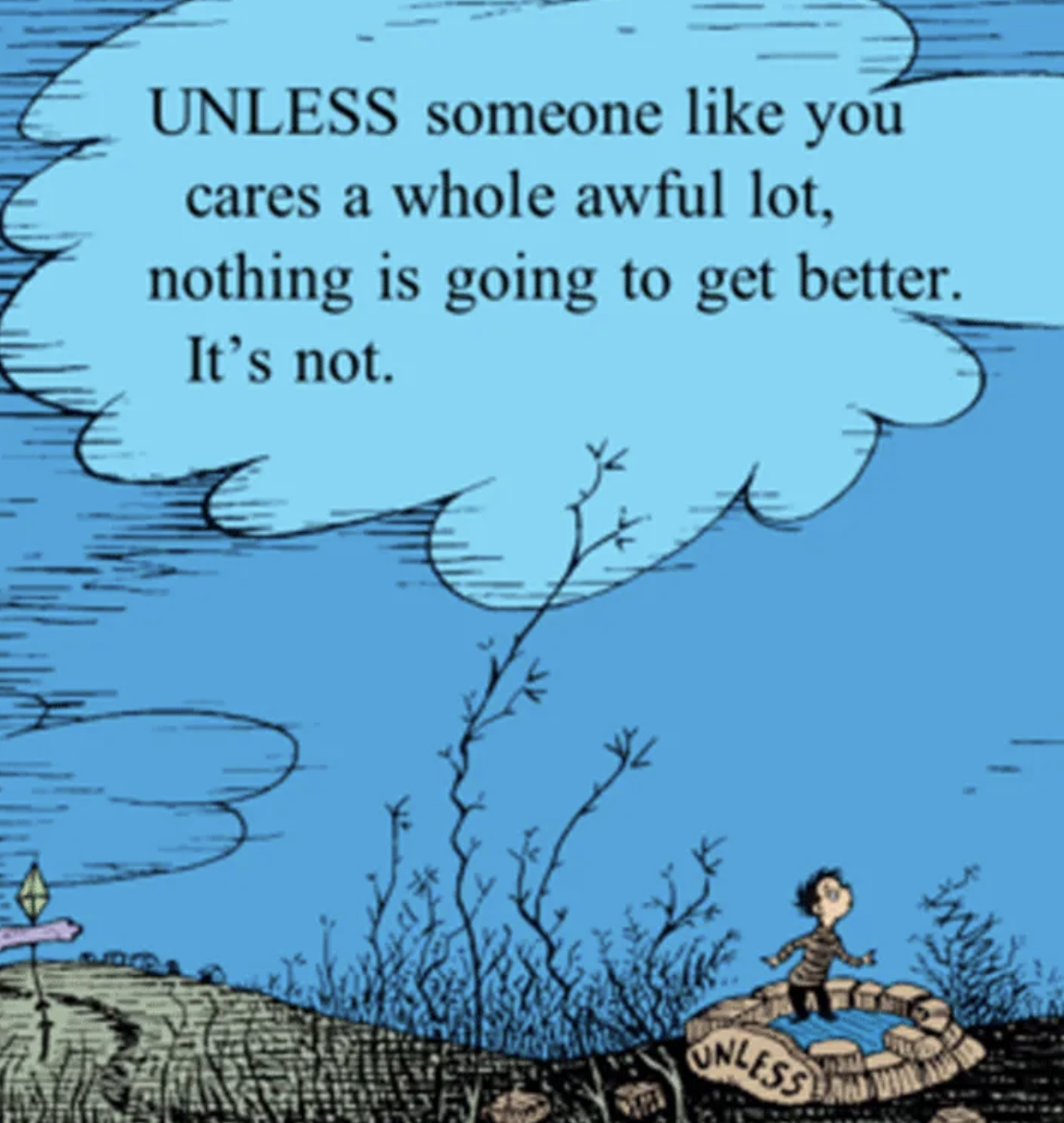

Unless…

The Onceler, having told their story, ends with a call to action to the reader. The character of the Onceler, once focused only biggering their business, now seems more reflective and somber. They tell the reader this cycle will happen over and over again . . . unless.

“Unless someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better.”

And the Onceler is right. That statement isn’t only a call to action. It’s a principle echoed by a Nobel Prize-winning economist.

“Ecological systems rarely exist isolated from human use…Governing natural resources sustainably is a continuing struggle…”

I’m a product manager by trade. I’ve written a lot of problem statements. I feel for my engineers, designers, UX folks and anyone who has to read them. Rarely are my problem statements as succinct, eloquent and powerful as the introduction to this paper.

For some context: last week, we introduced Elinor Ostrom, who the Onceler seems to be channeling in their call to action. Ostrom won the nobel prize in economics for her work showing the tragedy of the commons, like the example described by the Lorax, is not inevitable.

In this paper Ostrom paired up with ecologist Harini Nagendra and looked at data about what works when it comes to preserving forests. The paper was published by the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Three patterns of successful governance stood out: all had a theme of local voice, local monitoring and local governance.

1. Rules for forest commons should fit local circumstances.

Top-down policies on sustainable forestry often failed because they imposed one-size-fits-all rules. These rules didn’t match the local ecosystem, economy, or culture. Forests improved when people on the ground created their own rules that made sense for their forest. Ostrom calls this rule “congruence with local conditions.”

Cautionary Tale: In India’s Baikunthapore Reserve Forest (BRF), a government-run protected area, the forest experienced continued illegal logging despite formal rules and monitoring by officials. The rules weren’t tailored to local needs, and the community had no voice, resulting in widespread degradation.

From the paper: “…the actual rules and mechanisms used to manage forests on the ground mattered more than the formal ownership.”

Understanding what doesn’t work brings us to our next pattern, what does …

2. Forest commons must be monitored locally

One of the strongest findings in the study was that local monitoring was linked to healthier, more sustainable forests. Again, the word local is key. Outsiders are relatively ineffective. When neighbors are empowered to walk the boundary and keep an eye on things, monitoring works.

A good example: In Nepal’s buffer zones near Chitwan National Park, communities with recognized monitoring responsibilities saw regrowth, even in politically unstable periods. Specifically: Forests monitored by local users had significantly higher forest density (as measured in basal area and DBH) compared to those without local monitoring. For those hankering for data, check out Table 3 in the study. It shows local monitoring was statistically significant for improved outcomes.

Lastly, we need a Lorax, someone to speak for the trees. In more professional language…

3. Forest commons need the right to organize and punish defectors

Even if communities had good ideas and the will to act, it didn’t matter unless they had recognized authority to make and enforce rules. This adds to Coase’s work. Coase proposed that privatization was the only real solution to the tragedy of the commons. The government's only role role was to clearly decide and define who gets what.

Ostrom says: yes, but the government should “privatize” common resources by giving control and enforcement power to local communities. Forests in Nepal, for example, performed better because user groups had legal standing to manage them. Forests managed by governments alone, with no role for locals, were far worse off.

Stunning Example: Ostrom and Nagendra found that in Nepal, local user groups had legal recognition and secure tenure rights, even though the land was technically government-owned. During a decade-long civil war (1996–2006), central authority collapsed in many rural areas. Yet forests managed by these local groups didn’t fall into chaos. In fact, forests continued to regrow, thanks to local leadership and shared norms. These communities didn’t wait for top-down orders. They already had the power, legitimacy, and local trust needed to enforce their own rules and protect their resources.

Conclusion

The Lorax gave us poetry. Ostrom and Nagendra gave us proof. They showed that when communities have a real say, when they can write the rules, monitor and enforce them, forests don’t just survive, they thrive. Forests can regrow and provide valuable resources even in the face of poverty, conflict, and weak central governments. The tragedy of the commons is not inevitable. It’s a warning. Ostrom and Nagendra’s work is a playbook on how we can write a different ending. But only if someone like you, a local, cares a whole awful lot.

In the words of the Oncler

“Plant a new Truffula. Treat it with care.

Give it clean water. And feed it fresh air.

Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack.

Then the Lorax

and all of his friends

may come back.”

Added Notes

Illustrations and quotes from The Lorax by Dr. Seuss.

You can see some of the amazing illustrations here

A full PDF of the Lorax can be found here

Extra Credit

Special thanks to a reader who, after reading Economics by Quint the golden retriever: Sustainable Systems sent me a podcast.

Is this a good example of what Ostrom is talking about in governing the commons?

Planet Money: The Great German land lottery.

YES! It’s a great example. And this episode nails an element of today’s post too: the importance of the process beeing seen as fair by locals. Thanks reader! <3